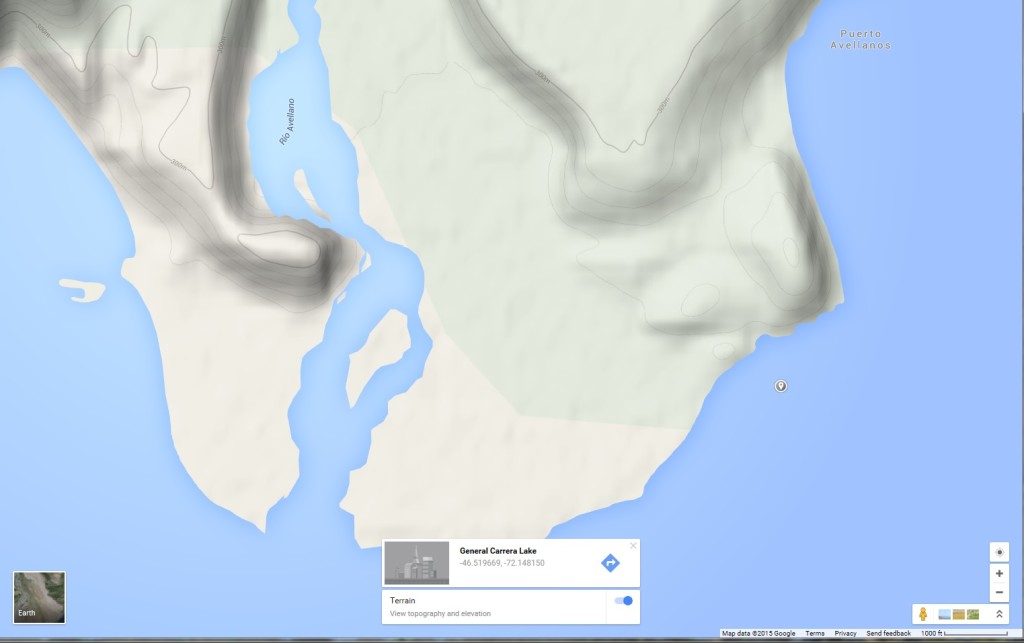

General Carrera Lake in Southern Chile (Click to Enlarge)

-by Jay Murdock, SDKC Safety Editor

The Accident

In December of 2015 a San Diego Kayak Club member sent out a National Geographic story of an incident earlier that month involving well-known world-class outdoor adventurers. Six highly skilled and experienced men, including the founder of North Face were kayaking the northern shore of General Carrera Lake in southern Chile, and were caught 600 feet (a distance of two football fields) from shore in sudden high winds while rounding a large peninsula. Within 10 minutes the conditions changed from calm/no wind, to gale-force winds creating six-foot-high, closely set waves. ** (See link below to read the story first)

An Accident That Could Happen to Anyone

No one, regardless of experience and skill level, is immune from an accident. In most cases an accident is caused by a series of mistakes, even with those events related to severe weather. For instance, the FAA has found in studying air plane accidents, when human error was a factor, there were two or more reasons, or mistakes, that typically contributed to the accident. They found in almost every case the accident could have been avoided had different decisions been made. And it was found that pilots who took chances were more likely to be involved in a tragic accident. By looking closely at the Chile tragedy, we can learn from what happened, and maybe avoid an accident in our future.

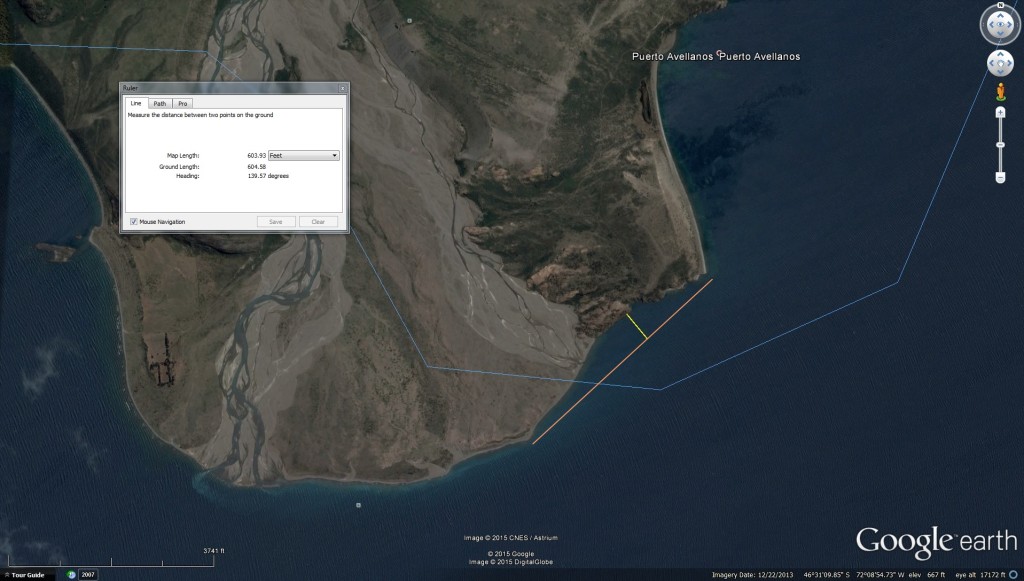

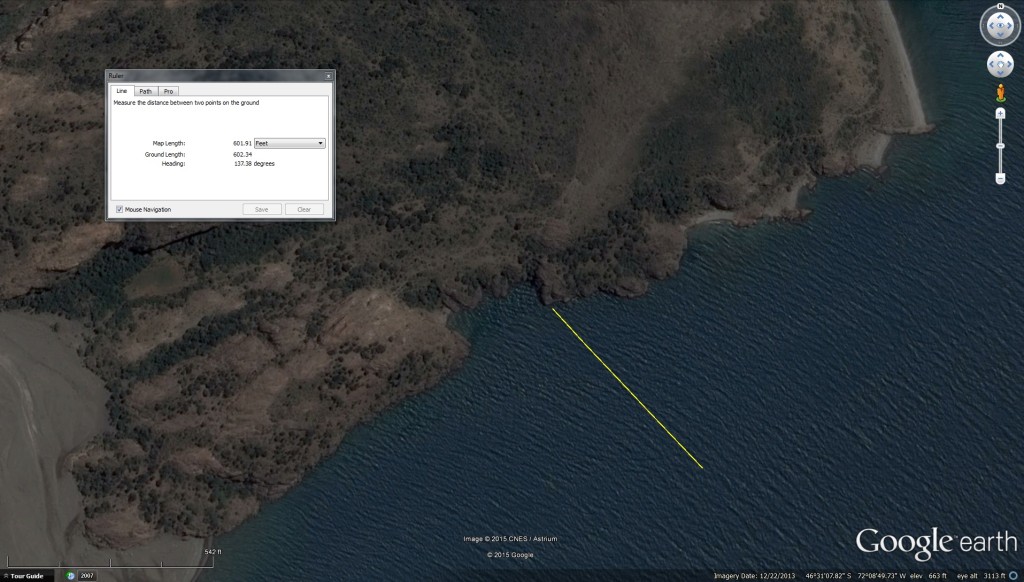

(Click to Enlarge)

Why They Were So Far From Shore

By examining the incident report, satellite photos and topo maps, it is evident just where the tragedy took place. Looking at the 3 maps above, the most likely reason the group was 600 feet from shore when the winds came up is that they were taking a direct line between two jutting land points in order to save time or some other reason, but it does not appear they were avoiding shallow water. In the above map/left side, the six men were rounding the peninsula going east, and were caught by the sudden wind somewhere in the area of that map marker off shore. You can see why they decided to “cut the gap” along the curved shoreline, taking a direct route across the opening in order to round the point on the far right side of the map. The two satellite photos have a yellow line I’ve added, showing the 600 foot distance they were from shore, a line which would be perpendicular to their line of travel across the opening (orange line on the expanded area photo). The far right photo clearly shows 4 emergency landing sites along that steep rocky shore, places to exit the water before rounding the point on the far right of the photo (the place where some in the group made it to).

The 100 Foot Safety Rule

Crossing large open water on a lake or bay should take several factors into consideration. Group size, boat traffic, water temperature, wind and weather conditions/predictions, working condition of your equipment, time of day, and capability of each in the group. Unless you absolutely have to venture far from land, it is always much safer to stay close to the shore. It may add another mile or so to arrive at your destination, but taking the safer route is always the wise choice.

By simply “Hugging the Shore” not more than 100 feet away keeps you within that distance where you can reach a landing point quickly, while staying just far enough off shore to avoid rocks or other obstacles just under the surface. 100 feet is about six lengths of a sea kayak. By staying close to shore you are hopefully within two minutes of landing, given that you may need to paddle along the shore to find a place. Mild, prevailing winds are not the concern here. If a sudden wind starts up, or a mild wind suddenly increases, that is the time to start moving toward shore and looking for an exit site. If the best exit point is upwind, you will need to make that turn before the wind gets too strong. Closing that distance part-way will increase your “Margin of Safety”, and will let you get in faster if the wind continues to increase in velocity. Knowing where you are, and the best places to land will allow you to make quick and reliable decisions for the best outcome. In this case under examination, from the account in the article, the two men were being taken by the wind and current out into the lake. Had the group been hugging the water’s edge, that curved shoreline area was most likely in a partial lee from the wind, and not in the current (many large lakes have currents caused by wind, water temperature variants, and inflowing rivers, and the shoreline typically slows down a current due to friction).

Hugging the Shore

Resources to Help in Planning and Executing a Paddle

Topo maps are a great help in determining safe places to land on shore, but Google Earth can often be more help in actually seeing what is there. By looking at the topo map and Google Earth photos above, you can quickly see this advantage. Topo maps show the obvious contours of the land, and show the hill on the right side of the peninsula, the place where it was rocky at water’s edge. Google Earth not only lets you see the Lat/Lon and elevation as you move your curser over the terrain, but it lets you look at the features from near-ground/water level as you move along a proposed route. Before you leave on an extended paddle to a new location, study both in order to determine your best places for an emergency landing, and carry a print-out of critical areas along your route. Before each leg in a trip, go over the maps/photos of those areas in order to refresh everyone on an emergency plan. Carry a reliable means of communication. In remote areas, that means a satellite device. If possible, find out what the weather will be that day, but at least know what could occur by knowing the wind patterns for that area. Wind is the most difficult thing to predict, which is why the NWS will not give the wind speeds more than two days out. And wind can suddenly shift directions, which could result in a capsize. The area in Chile where this incident took place is known for sudden, fast-rising, high winds.

Other Considerations

- Wear the right safety gear and protective wet/dry suit for the water temperature, covering your whole body with one immersion suit (our legs comprise the largest percentage of skin area of our body, and a one-piece suit also protects your mid-section). Protective clothing will also help stave off shock from sudden cold water immersion. If you find yourself suddenly in cold water, you have about two minutes before you become numb and unable to function, so act fast. Know how to perform the “Heel Hook” reentry and a “Quick-Tow” if you cannot get back in your boat with two attempts. If both of these procedures fail, or you are being blown off shore, then a back-stroke swim to shore is your last resort, followed in by the other kayaker instructing you which direction to swim.

- Constantly check your equipment to make sure everything is working properly. If not, stop and fix it before proceeding. Carry a back-up and repair kit for the most critical items. One very important safety item to have is a paddle tether. There are choices in tow lines. My quick-tow line is deck mounted, and always right in front of me ready to use. It has a carabiner at one end for a quick attachment to the other boat. I have a small “jam cleat” mounted on my deck just behind me on the right side for a quick attachment of the other end, and a quick release if needed. The line is small diameter but strong, and long enough to have two feet over my lap, and a four foot gap between the boats.

- During each paddle, especially in a new location, observe the shoreline as you proceed in order to note the immediate best exit point. The more you pay attention to that, the more it will become an automatic observation.

- One more critical thing that is sometimes not considered essential: Fueling up prior to, and during the paddle with high-energy food. Even though adrenalin kicks in during an emergency, having enough energy to deal with high levels of exertion, and guarding against hypothermia is a vital consideration. That also means staying hydrated with water from an insulated container on cold air temperature paddles. More information on all this can be found on the San Diego Kayak Club website in the Safety articles (which have been given a “Thumbs Up” by the local Coast Guard).

Conclusion

It is most likely the group had been paddling close to shore that day as they went around the peninsula, until they came to the place where the shoreline fell away to their left. Seeing the other point of land to the east, they decided and assumed the sunny and calm conditions would hold while they crossed directly to that point, which was less than a mile away. Relying on their vast experience and skill level, they took a chance because it seemed easy. For those men on the lake that day, the difference of 500 feet distance from shore may have been the difference between life and death.

**- Details of the incident can be found with the following link: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/12/151213-doug-tompkins-chile-north-face-rick-ridgeway-patagonia-yvon-chouinard-death-general-carrera-lake/

![CPat18[1]](http://www.sdkc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/CPat181.jpg)